Wall Street has been here before—or thinks it has. Two and a half decades ago, investors were dazzled by the dawn of the internet, throwing money at anything with “.com” in its name. That speculative fever eventually collapsed, wiping out $5 trillion in market value and sending a generation of day‑traders back to their day jobs.

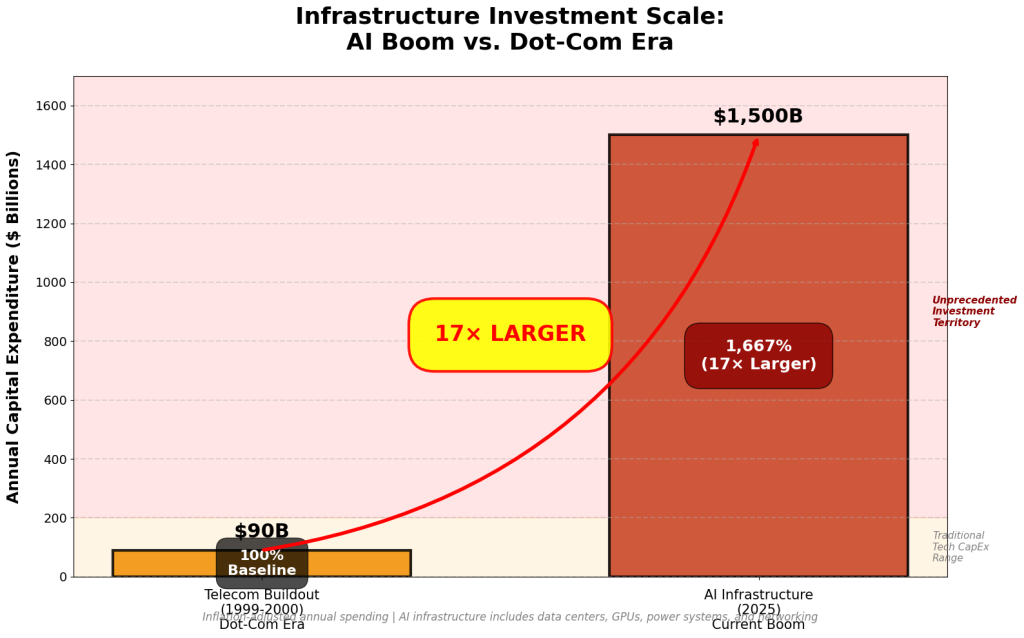

Now, as artificial intelligence surges into boardrooms, balance sheets, and public consciousness, skeptics argue that history is repeating—only this time, on a far greater scale. Société Générale’s Albert Edwards, a strategist renowned for his accurate call during the dot‑com bust, recently warned that the AI frenzy may already be 17 times larger than 2000’s bubble BizToc summary of MarketWatch.

At first glance, the claim sounds hyperbolic. But when you unpack the numbers—valuation multiples, cap‑ex intensity, and market concentration—the comparison begins to look uncomfortably plausible. The question isn’t whether AI is a transformative technology. It is. The question is whether investors, in their collective sprint to cash in, have priced AI’s future decades ahead of reality.

Measuring the Mania

Market concentration: Today, the largest U.S. tech names account for almost 40% of the S&P 500, compared with 29% at the dot‑com peak. That level of concentration is rare and usually dangerous, because when a handful of companies support the market, they also shape its downside.

Valuations: Nvidia, the poster child of AI, trades at a market cap above $3 trillion—larger than most countries’ GDP. Across the sector, metrics like the Shiller CAPE (a cyclically adjusted P/E ratio) have smashed old records, sitting far above the frothy territory that preceded the 2000 crash.

Capital spending: The sheer amount of money flowing into AI infrastructure dwarfs anything seen before. Consulting firm IDC pegs global AI cap‑ex at $1.5 trillion for 2025 alone. By contrast, the telecommunications build‑out during the late 1990s—the so‑called “dark fiber” boom—peaked near $90 billion per year in today’s dollars.

By those measures, Edwards’ 17x multiple is less outlandish than it first appears.

Echoes of 1999

The similarities between the current cycle and the dot‑com era are striking:

- Runaway optimism. Investors are extrapolating AI adoption curves at breathtaking rates, just as they once assumed every new website would become a billion‑dollar business.

- Retail speculation. During the internet bubble, small investors poured into day trading. Today, social media and zero‑commission brokerages have amplified similar behavior around AI stocks.

- Infrastructure arms race. Just as telecom firms massively overbuilt fiber to prepare for internet demand that didn’t yet exist, today’s hyperscalers are rushing to build AI‑optimized data centers. Energy demand alone could rise by 30% in the next decade to support the expansion, creating both opportunities and bottlenecks.

But the story isn’t simply a rerun.

What’s Different This Time

Three structural differences stand out:

Profitable incumbents, not fragile start‑ups. In 2000, Pets.com and Webvan had little more than PowerPoint slides and venture funding. In 2025, the AI boom is led by companies that generate hundreds of billions in cash flow annually—Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Nvidia. That financial firepower buys them time and resilience.

Real revenues. Microsoft’s AI‑powered Azure services are on an $86 billion run rate. Nvidia’s CUDA software ecosystem locks developers in. These are genuine businesses, not revenue projections on a napkin.

Industrial policy tailwinds. U.S. and European governments are underwriting billions in semiconductor subsidies, power projects, and grid expansion. That political support reduces the risk of wholesale collapse—though it could also fuel inefficient overbuilding.

Cracks Beneath the Surface

Even with these differences, there are reasons for caution. History suggests bubbles burst when expectations flatten while valuations remain stretched.

- Earnings risk. MIT estimates that 95% of corporate AI pilot projects fail to deliver measurable ROI. If deployment proves slower than expected, revenue growth could disappoint.

- Overcapacity. Companies are investing trillions into AI chips and data centers. But if demand doesn’t keep pace, utilization may fall, mirroring the “dark fiber” debacle.

- Policy and regulation. Export controls on GPUs, potential limits on energy usage, and antitrust scrutiny of Big Tech could all limit monetization.

- Competitive risk. Cheaper open‑source models could undercut incumbents and drive down pricing power faster than Wall Street expects.

In other words: AI will change everything—but maybe not on the schedule investors hope.

Where Investors Might Still Find Opportunity

For all the froth, not every stock is untethered from reality. The key is distinguishing between hype‑fueled plays and companies positioned to benefit even if AI develops more slowly.

- Nvidia (NVDA): Cornerstone of the AI supply chain, but now branching into networking and software. Still volatile—but with a durable moat.

- Broadcom (AVGO): A quieter chipmaker producing custom AI silicon for the big cloud players. Valuations are more modest than Nvidia’s.

- Microsoft (MSFT): AI runs through Office, Azure, and GitHub Copilot. Expensive, but backed by sticky enterprise subscriptions.

- Super Micro Computer (SMCI): Supplies servers configured for AI workloads. Flexible across architectures, giving it a hedge against chip supplier shifts.

- Schneider Electric (SBGSY): Produces the electrical equipment data centers require. With AI workloads consuming up to five times more power than traditional computing, Schneider could be one of the most reliable long‑term beneficiaries.

The Long View

The lesson from 2000 is clear: the internet was real, but valuations outran reality. Investors who piled into any company with “dot‑com” in its name got burned, while those who stuck with infrastructure enablers—Cisco, Intel, Amazon—captured enduring value.

The same may hold true today. AI is here to stay. But investors betting on an instant productivity revolution may be setting themselves up for disappointment. The winners will likely be the companies that provide the plumbing—chips, servers, power, and cloud—and those with business models resilient enough to weather the volatility ahead.

The “17 times” headline conveys a simple truth: the AI bubble, if it bursts, won’t just wipe out paper fortunes. Given how deeply AI is now embedded in equities, capital markets, and corporate strategy, the fallout would ripple through the global economy.

As Edwards warns, every bubble ends badly. The challenge for investors is discerning whether AI’s path resembles the 1999 dot‑com crash—or the early years of an industrial revolution that will reshape the economy for decades.